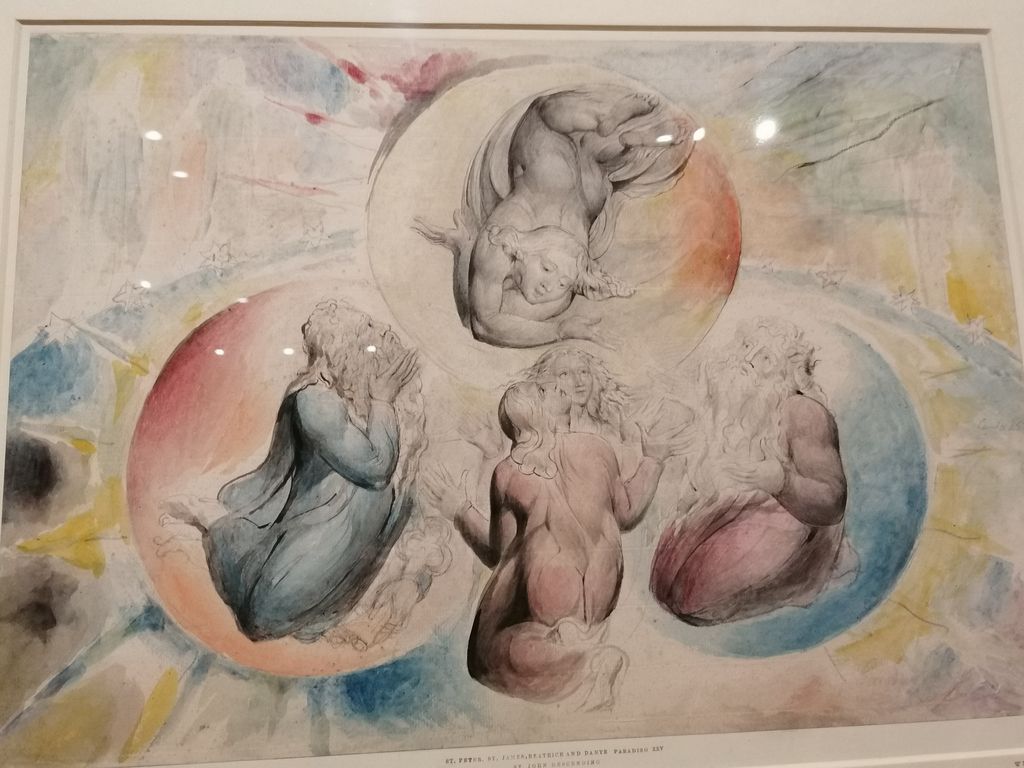

St Peter, St. James, Beatrice and Dante, St. John Descending - Tate Britain Exhibition 2020 - photograph by writer.

In your bosom you bear your heaven and earth and all you behold; tho'it appears without, it is within, in your imagination'.

'Like many of Blake's statements, this can seem bewildering and mystical at first glance, but when we reread it we see that Blake was being clear and concise.' (John Higgs, Blake vs the World, Ch. 4).

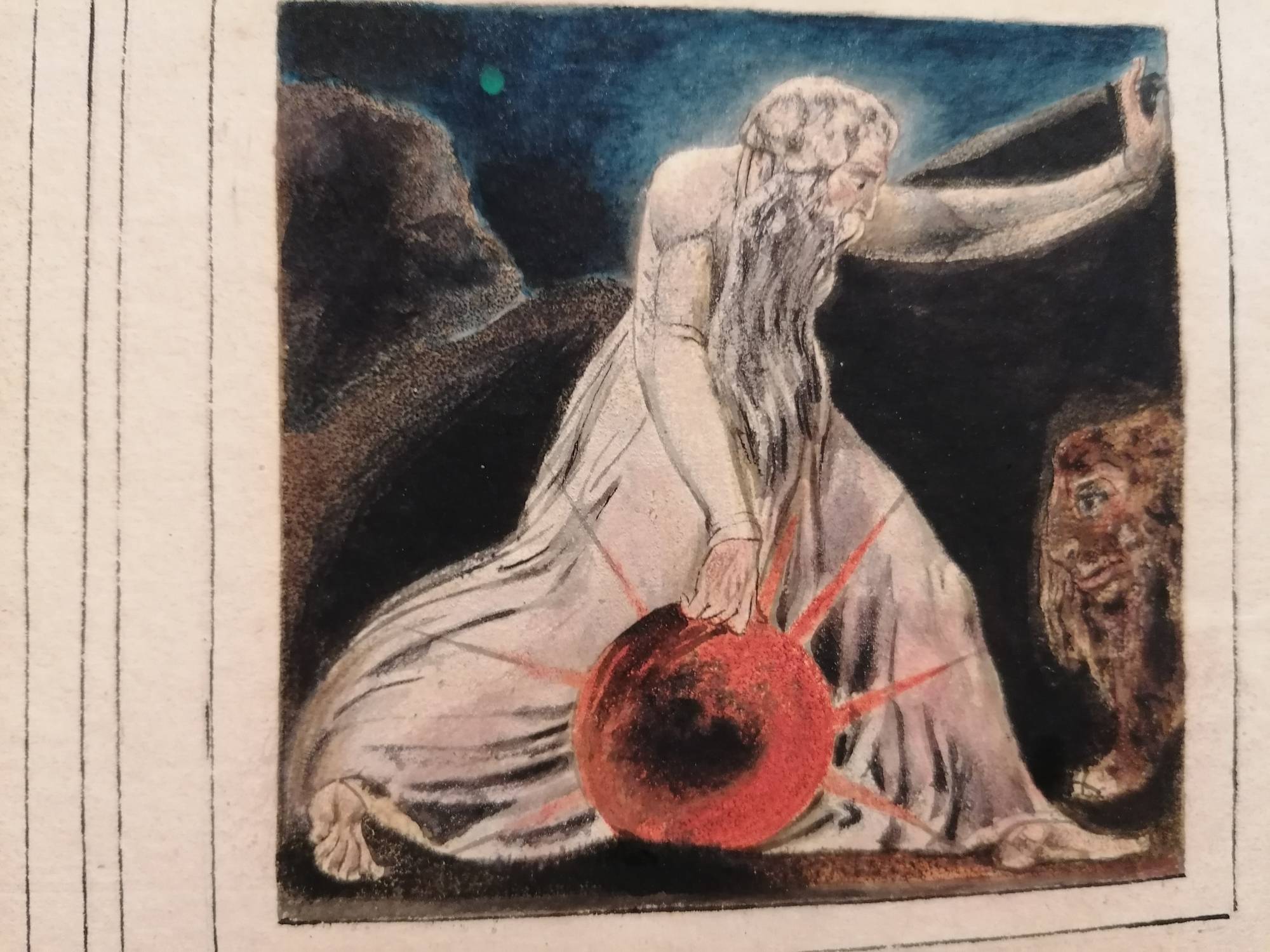

All that exists in the material world started as an idea in someone's imagination. Now that we live in such a provided-for physically built environment, and since the industrial revolution, its possible to believe in only the material world, things we can see and touch, which are already there. Blake foresaw the demise of belief in the inner creativity, the mystical, spiritual or creative experiences; just as the demise of religious dogmas was in the ascendent during the Enlightenment and Newton's physics brought the age of scientism. In The Book of Urizen Blake illustrates his concern that reasoning and laws of science limit infinite possibility. [My post on Urizen]

"Spread a Tent, with strong curtains around them

Let cords and stakes bind the void

that Eternals may no more behold them."

They began to weave curtains of darkness

They erected large pillars around the Void

With golden hooks fastened in the pillars

With infinite labour the Eternals

A woof wove, and called it Science

Much of Blake's poetry and artwork is built upon his insight that "without contraries there is no progression. Attraction and Repulsion, Reason and Energy, Love and Hate are necessary to Human existence."

"...contraries and oppositions - love and hate, expansion and contraction, opaqueness and translucence, reason and energy, attraction and repulsion, these are the poles of his world, where 'Without Contraries is no progression'. He establishes pairs and couples within his poetry and his art; his painted objects are often placed in symmetry with each other, just as his epic verse is heavily imbued with parallelism and antithesis. In his greatest work he creates giant forms that contain his own contradictory impulses and private oppositions; he establishes a 'bounding line of art or poetry that does not unite contraries but allows them to exist in harmony beside each other." [Blake Vs The World. Find page]page]

The very definition of one aspect of being implies the other exists; described by the 600BC philosopher Lao Tsu:

'Being and non-being create each other.

Difficult and easy support each other.

Long and short define each other.

High and low depend on each other.

Before and after follow each other.'

Any concept has its own accompanying concept to define the degrees of either. Mathematica Universalis (http://heurist.org) works with conjugates, listing abstracts such as 'actuality and possibility', 'enfold/unfold' amongst many. In the context of their extensions into humanity, he further describes them as having depth as the 'male' agency of focus and action, and the wider scope, the 'female' societal integration. Depth and scope are tangential to each other.

The Philosophy of Anaxagoras - 500BC - c.428BC

Blake's 'contraries' were expressed as the harmony of the relationship of opposites; a yin-yang balance of conditions. e.g. hot/cold, near/far. The terms are not opposites, but conjugates; one aspect of a condition, always being in a certain proportion to another aspect. Abstractly, any proportion of an experienced or observed condition, will have a counterpart which is less or more of its conjugate. They are not always in balance, rarely, as their very definition is bound by their distance from their conjugate. Anaxagoras understood the interrelation of all things, by their having elements of their counterpart. "Anaxagoras apparently realized those opposites not as "qualities," but as things as things of spatial extensiveness.’"

Whilst imagination is the root of everything, within all developed civilizations, a development which harms humanity sometimes happens. British philosopher Owen Barfield (worked with C S Lewis and J R R Tolkein), said we must take responsibility with imagination. In modern times responsibility is only now being taken by individuals into the evils which science has imagined and now is being meshed with us: imaginative ideas of mad scientists, biotechtopian plans for a technofied humanity with no sensible control.

Further Reading on the imagination and 'contraries'.

Returning to the Essential: Selected Writings of Jean Bies

Chapter 19 : The Harmonics of Unity.

'...Antagonisms are complementary, that the entire universe, in its microscopic aspects, is where these never-ending transmutation of a unique energy, of every more complex attractions and repulsions occur. It results in the unification of the contradictory aspects of Reality: continuous-discontinuous, seperable-insperable, living-nonlivng, permanent-impermanent. It reveals that all phenomena are of a communicative and interactive nature.'

'At the very heart of the matter recent explorations have revealed other conciliations, such as the one of waves and corpuscles, in which one aspect or another prevails according to the situation. The “inseparability” of phenomena illustrates the fact that although very distant, these phenomena can act among themselves as if there was no distance between them. It makes you wonder whether, at a certain level of the Real, instantaneous relationships exist between all the points in the universe.'

[The aspect William Blake refers to is the natural regulation of one aspect being defined by the lack or difference. Warm is only so because it has less cold. Light is only so because it has less dark... etc.]

ONCE ONLY IMAGN'D - Chapter 7 - William Blake vs The world

To understand more of Blake's reasoning on imagination, we can consider his inspirations in relation to the philosophy of his era. Ideas were abounding in the 1700s; in particular as people refused to believe their church teachings that man is a sinner. Religious images were a major part of his engraving career, as commercial art was still religious, but he incorporated his own imaginative ideas more intently over time. He was an idealist who loved nature and railed against slave labour and the technotronic future, as he glimpsed its coming through the developing industrial revolution.

"I must Create a System, or be enslav’d by another Mans"

The Wisdom of Angels - JERUSALEM Tobias Churton- Chapter 2

He was influenced by Swedenborg who created a new 'church' in the year of Blake's birth to create a new vision of Christianity than the Anglican Church; maybe similar to the Morovians whom his mother followed, and may have taught Blake related philosphy. Jacob Boehme wrote Mysterium Magnum 1623: was philosopher of the divine, in the alchemist era, a huge influence on Blake. All things contain the 'other' of their existence in degrees of balance. Blake's "contraries". And his inspiration for Heaven and Hell. During revolutionary times, we can see how relevant such ideas were. The world wasn't ready for either of them.

Blake's "four fold vision" seems to represent states of consciousness, similar to those explored in modern times by Leary

The French poet Charles Baudelaire called it ‘the queen of the faculties’ and insisted that ‘Imagination created the world’. Pablo Picasso told us that ‘Everything you can imagine is real’. In the eyes of the Pulitzer Prize-winning American poet Wallace Stevens, ‘imagination is the only genius’. In 1931, Albert Einstein wrote that:

‘"Imagination is more important than knowledge, For knowledge is limited, whereas imagination embraces the entire world, stimulating progress, giving birth to evolution.’"

Some western tradition (philosophers, academics) argue that the imagination is of little value compared to the rational intellect, and is just the brain at play. In Platonic philosophy, imagination belonged on the lowest rank of mental faculties. Aristotle also argued that ‘imaginings are for the most part false’. Later philosophers took a similar dismissive view. The English philosopher John Locke argued that there ‘was nothing in the mind that was not first in the senses’. The German philosopher Edmund Husserl did not see imagination as a ‘productive’ act, because 'measurable things that exist externally, in time and space, were important in a way that things that exist internally were not'. [This belies the fact that all the productions of civilization emanated from imagination, then systems were enacted by followers; just as we have our corrupted governments now following corrupt corporations and bankers.]

Jean Jaques Rousseau in 1749 realised man was born good, only corrupted by institutions and his philosophy changed everything. Rousseau's 'Social Contract' of 1762:

"man is born free and everywhere is in chains"

a quote from his book Julie or The New Heloise in 1761, exploring the ideas. The Vatican banned it, though many people read it as it was available for hire by hour or day. This enlightenment took hold of the people and led to the French Revolution.

Gottfried Leibniz had realised in 1710 we must be living in the best of possible worlds, and if that was not the case, then it must be the institutions; in line with Rousseau's thinking. Now we know it IS the institutions, especially banking, which enslaves us.

Nothing is invented without someone imagining it, then bringing it into being with or without technology.

Whilst imagination is the root of everything within all developed civilizations, a development which harms humanity sometimes happens. British philosopher Owen Barfield (worked with C S Lewis and J R R Tolkein), said we must take responsibility with imagination. [Find it] [In modern times responsibility is only now being taken by investigative journalists into the evils which science has imagined and now is meshed within almost every aspect of our lives: original imaginative ideas of mad scientists, with no sensible control.]

Extracts from 'The Philosophy of Anaxagoras: An Attempt at Reconstruction' by Felix M. Cleve

With quotations of Anaxagoras: .. .'the mixture of all things:'

of the moist and the dry,

of the warm and the cold,

of the bright and the dark

(since also much earth was therein ),

and, generally, of seeds infinite in quantity,

in no way like each other.

... the dense is severed from the rare,

the warm from the cold,

the bright from the dark,

and the dry from the moist

'These ultimate elements are exemplified by the pairs of opposites mentioned in the extant fragments. Every pair of these opposites corresponds to another field of sensation, or, to say it with an Aristotelian term, is "specific as to the senses", '

'Anaxagoras apparently realised those opposites not as "qualities," but as things as things of spatial extensiveness.’‘... This is a fundamental discovery, and Anaxagoras understands it as the basic and primary interrelation of the elements. He declares:

There is no isolated existence, but all [things] have a portion of every [element].

The [elements] in this one cosmos are not separated from one another.

'That is to say:'

There is no thing containing particles of the bright and the dark (color) which would not contain as well, particles of the warm and the cold, (temperature) particles of the rare and the dense, or, what amounts to the same thing, of the light and the heavy, (pressure) particles of the moist and the dry, (other haptic qualities) etc

P. 10, 11. "THE GREAT" AND "THE SMALL"

‘The fundamental statement that there is no isolated existence is true also in that field in which the opposites are named, "the great" and "the small." This could be the field of spatial extensiveness as such.

Anaxagoras seems to have been aware also of the fact that the optic sphere includes not the quality of color alone, since there is also colorless extensiveness.’

In this connection must be mentioned Anaxagoras' experimental proofs that the air, though colorless and, therefore, invisible, is not a "nothing," not a vacuum:

'And since also the portions of the great and of the are equal in number, also in this respect all [elements] would be in everything, and isolated existence is impossible.'

'Consequently, there is no smallest nor greatest:

For of the small there is no smallest, but always a smaller one. . . but also of the great there is always a greater one. And it [sc., the great] is equal to the small in number.'

'For an absolutely "smallest" would contain no great particles at all, and an absolutely "greatest" would contain no small-particles at all. Such an "isolated existence," however, is out of the question: Even "the most great" is always "the least small" as well, and vice versa.'

Hence

"With reference to itself,

each thing is both great and small